HNC Photography, IFC - Coursework, Introduction to Film Culture Blog, Part five - Suspension of disbelief, Project 1 - Ideas and beginnings

Cinema and Adapting Literature: The Go Between and Captain Corelli’s Mandolin

The Go Between

P. Hartley’s The Go Between (1953) and its film adaptation, which was released in 1971 and directed by Joseph Losey, differ in terms of the context of the start of the movie and the first two chapters of the novel. The novel is narrated by Leo Colston, an elderly man who recounts his memories of visiting Marcus Maudsley, a school friend. The narrative itself is highly nostalgic and extremely detailed, establishing the context of the visit and providing an insight into who Leo actually was, evoking a response from readers that is emotive and tethered to his personal tragedies. Similarly, the reader is encouraged to examine Leo’s experience via his perspective: “…my buried memories of Brandham Hall are like the effects of chiaroscuro, patches of light and dark…” (Hartley, 2004). It would be impossible for the movie to present such an opening in the same level of detail and it is also necessary to acknowledge that the image that appears on screen provides an insight into the director’s interpretation of the first two chapters. Indeed, Bordwell and Thompson (2003) point out that auteurs do not tend to write the scripts for their movies but instead assert their authority over the narrative and aesthetics of adaptations. This is certainly evident in the divergence between book and film. For example, there is no preamble, narration or introduction to the older Leo but rather the film begins with his arrival at Brandham Hall. In effect, this limits the knowledge of the audience, framing Leo’s thoughts instead through the dialogue between the guests the evening he arrives. However, it should be noted that the use of the camera does provide an insight into his experience of the space within the house, framing and then double framing him within doors and on staircases, acknowledge the development of the self within the new environment as he explores it (Bowman, 1992). Despite this, there is a clear disjunction between the tone and content of the book and that of the opening scene in the film adaptation.

P. Hartley’s The Go Between (1953) and its film adaptation, which was released in 1971 and directed by Joseph Losey, differ in terms of the context of the start of the movie and the first two chapters of the novel. The novel is narrated by Leo Colston, an elderly man who recounts his memories of visiting Marcus Maudsley, a school friend. The narrative itself is highly nostalgic and extremely detailed, establishing the context of the visit and providing an insight into who Leo actually was, evoking a response from readers that is emotive and tethered to his personal tragedies. Similarly, the reader is encouraged to examine Leo’s experience via his perspective: “…my buried memories of Brandham Hall are like the effects of chiaroscuro, patches of light and dark…” (Hartley, 2004). It would be impossible for the movie to present such an opening in the same level of detail and it is also necessary to acknowledge that the image that appears on screen provides an insight into the director’s interpretation of the first two chapters. Indeed, Bordwell and Thompson (2003) point out that auteurs do not tend to write the scripts for their movies but instead assert their authority over the narrative and aesthetics of adaptations. This is certainly evident in the divergence between book and film. For example, there is no preamble, narration or introduction to the older Leo but rather the film begins with his arrival at Brandham Hall. In effect, this limits the knowledge of the audience, framing Leo’s thoughts instead through the dialogue between the guests the evening he arrives. However, it should be noted that the use of the camera does provide an insight into his experience of the space within the house, framing and then double framing him within doors and on staircases, acknowledge the development of the self within the new environment as he explores it (Bowman, 1992). Despite this, there is a clear disjunction between the tone and content of the book and that of the opening scene in the film adaptation.

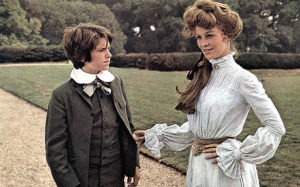

The importance of the lead female, Julie Christie as Marian Maudsley, is evident in the opening fifteen minutes of the movie as a result of her positioning as an object of desire. She is  continually framed by the camera in poses that emphasise the way Leo appears to be mesmerised by her. However, Leo is always perceived to be looking up to her, thus constructing other ideological meanings. Napper (2012) notes that representations of class and gender are often conveyed very clearly on film whereas that is not necessarily the case within the literature that they are adapted from and that is certainly the case here, but the perspective offered by the narrator and by the camera in the two respective mediums do not follow common paths. For example, the flawed memory of Leo draws attention to Marian’s beauty within his first impressions of her: “So that is what it is to be beautiful, I thought” (Hartley, 2004). In effect, this depiction of Marian in the movie does correlate with the way in which she is presented within the book. There is a coherence to the presentation of the character that translates effectively from memory within the text to actuality on the screen. In this sense, the way in which Marian is envisioned by Hartley does correspond to the book. The male protagonist, Alan Bates as Ted Burgess, does not appear within the first two chapters or in the opening scene of the movie but this is perhaps more effective given that Phillips (1999) notes that Leo is very much the outsider within the environment established as the primary location of both the book and the movie and this is clearly reflected in both. Ted would have arguably detracted from that. However, the characters do not quite respond to the vision constructed of them via interpretation of the narrative of the book because the interpretative freedom is removed from the reader as he or she becomes a viewer. As such this analysis suggests that reading the book prior to watching the movie actually has a significant impact upon the way in which the viewer responds to the film because it is likely that he or she has already envisioned how the narrative should be presented. The adaptation and revision of the literature is therefore wholly dependent on perspective, as Villarejo (2013,) suggests, and is clearly grounded in the issues of the era pertaining to such issues of gender and class, thus expanding upon the original appreciation for the story and its complexity.

continually framed by the camera in poses that emphasise the way Leo appears to be mesmerised by her. However, Leo is always perceived to be looking up to her, thus constructing other ideological meanings. Napper (2012) notes that representations of class and gender are often conveyed very clearly on film whereas that is not necessarily the case within the literature that they are adapted from and that is certainly the case here, but the perspective offered by the narrator and by the camera in the two respective mediums do not follow common paths. For example, the flawed memory of Leo draws attention to Marian’s beauty within his first impressions of her: “So that is what it is to be beautiful, I thought” (Hartley, 2004). In effect, this depiction of Marian in the movie does correlate with the way in which she is presented within the book. There is a coherence to the presentation of the character that translates effectively from memory within the text to actuality on the screen. In this sense, the way in which Marian is envisioned by Hartley does correspond to the book. The male protagonist, Alan Bates as Ted Burgess, does not appear within the first two chapters or in the opening scene of the movie but this is perhaps more effective given that Phillips (1999) notes that Leo is very much the outsider within the environment established as the primary location of both the book and the movie and this is clearly reflected in both. Ted would have arguably detracted from that. However, the characters do not quite respond to the vision constructed of them via interpretation of the narrative of the book because the interpretative freedom is removed from the reader as he or she becomes a viewer. As such this analysis suggests that reading the book prior to watching the movie actually has a significant impact upon the way in which the viewer responds to the film because it is likely that he or she has already envisioned how the narrative should be presented. The adaptation and revision of the literature is therefore wholly dependent on perspective, as Villarejo (2013,) suggests, and is clearly grounded in the issues of the era pertaining to such issues of gender and class, thus expanding upon the original appreciation for the story and its complexity.

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin (1994) was written by Louis de Bernieres, with the John Madden directed movie version being released in 2001. It has been subject to extensive criticism as a direct result of the very different endings. Taking the movie first, it concerns the invasion of the Ionian Islands in Greece by Italian forces during World War II, the latter of which included Captain Antonio Corelli. The final scenes of the movie concern his escape from the island after the Germans essentially massacre the Italians as traitors and leave him to die. His rescue at the hands of Mandras, his departure from Cephallonia and then the subsequent return to Pelagia renders it rather action packed and emphasises the impact of history on the nature of human lives during the war itself, drawing attention to the costs via the romantic element of the movie. However, the book, on the other hand, has a completely different ending and, having knowledge of the movie prior to reading the book, this contributes to a feeling of deflation. Instead of returning for Pelagia in the immediate aftermath of the war, Corelli does not return until he is in his seventies and is subject to her feisty responses when it becomes apparent that he had previously returned and mistakenly thought she had married and had a child (de Bernieres, 2011). The major departure from the original ending has been attributed to the lack of a resolution or consummation of the relationship in the book and the fact that this would not have translated well on film and having watched the movie first, it does not work on paper either. Although the context of the war complicates relations (Nowell-Smith, 1996), the anticlimax of Corelli keeping his distance from his love would not appeal to modern audiences.

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin (1994) was written by Louis de Bernieres, with the John Madden directed movie version being released in 2001. It has been subject to extensive criticism as a direct result of the very different endings. Taking the movie first, it concerns the invasion of the Ionian Islands in Greece by Italian forces during World War II, the latter of which included Captain Antonio Corelli. The final scenes of the movie concern his escape from the island after the Germans essentially massacre the Italians as traitors and leave him to die. His rescue at the hands of Mandras, his departure from Cephallonia and then the subsequent return to Pelagia renders it rather action packed and emphasises the impact of history on the nature of human lives during the war itself, drawing attention to the costs via the romantic element of the movie. However, the book, on the other hand, has a completely different ending and, having knowledge of the movie prior to reading the book, this contributes to a feeling of deflation. Instead of returning for Pelagia in the immediate aftermath of the war, Corelli does not return until he is in his seventies and is subject to her feisty responses when it becomes apparent that he had previously returned and mistakenly thought she had married and had a child (de Bernieres, 2011). The major departure from the original ending has been attributed to the lack of a resolution or consummation of the relationship in the book and the fact that this would not have translated well on film and having watched the movie first, it does not work on paper either. Although the context of the war complicates relations (Nowell-Smith, 1996), the anticlimax of Corelli keeping his distance from his love would not appeal to modern audiences.

There are many elements of the film adaptation that demand attention in relation to the narrative on which it is based. The first is the direction. Etherington-Wright and Doughty (2011) point out that an auteur may effectively construct an appealing narrative out of poor material and the disappointing anticlimax of the literary ending did provide scope for this. However, the rejection of the historical complexity of the aftermath of the war, which ultimately rendered the return of Corelli to Pelagia rather simplistic, instead taps into the tendency to construct grand narratives that emphasise romance over substance. In effect, Madden draws attention to the relationship between the characters as the focal point of the movie whereas this was not the case within the book. In the literature, Pelagia challenged the status quo and essentially does not need a man, thus facilitating the examination of the impact and outcomes of war.

In terms of casting, both Nicholas Cage’s Corelli and Penelope Cruz’s Pelagia have been appropriately selected for their roles and play them very well, with Cage capturing the nuanced persona of the Captain very well. However, Cruz embodies Pelagia, exhibiting her spirit and forcing the audience to believe in her ability to save Corelli as well as the development of a mutually important relationship. The casting of the film as a whole is very multi-national and as such help to pick up on the issues within the book of national and individual identity, for example the film and book portrays the Italian soldiers very much as individuals not the cold archetypal invader shown by David Morrissey’s German officer Overall, the adaptation (and casting) of the book to film here draws attention to the level of creative license available to directors and actors within its framework and the impact that it can have on the way characters and events may be presented.

In effect, the disjunction between de Bernieres’ book and its film adaptation renders neither outcome entirely satisfactory and does little to broaden the appeal or appreciation of the original story. If anything, it actively highlights its weaknesses rather than reinforcing areas of the narrative that pertain to the modern experiences of problematic relationships, cultural differences and the merging of the global and national, all of which are prominent issues within the book and movie. This highlights just how problematic adaptation can actually be when texts are not adapted properly.

Bibliography

Bordwell, D. & Thompson, K., (2003). Film Art: An Introduction. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Bowman, B., (1992). Master Space: Film Images of Capra, Lubitsch, Sternberg, and Wyler. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin, (2001). [Film] Dir. by J. Madden. USA: Universal Studios.

de Bernieres, L., (2011). Captain Corelli’s Mandolin. London: Vintage.

Etherington-Wright, C. & Doughty, R., (2011). Understanding Film Theory. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hartley, L., (2004). The Go-Between. London: Penguin.

Napper, L., (2012). British Cinema. In J. Nelmes ed. Introduction to Film Studies. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 361-398.

Nowell-Smith, G., (1996). Socialism, Fascism and Democracy. In G. Nowell-Smith ed. The Oxford History of World Cinema. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 333-343.

Phillips, G., (1999). Major Film Directors of the American and British Cinema. London: Associated University Presses.

The Go-Between, (1971). [Film] Dir. by J. Losey. UK: EMI Film Productions.

Villarejo, A., (2013). Film Studies: The Basics. Abingdon: Routledge.