Reflection on Seven Samurai, A Fistful of Dollars and Yojimbo, comparing the specific cinematic styles of the directors.

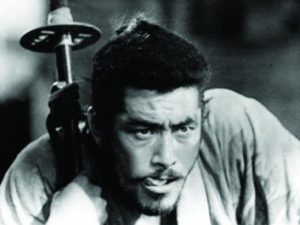

The films of Japanese auteur director Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998) came out of the aftermath of the Second World War; a time when Japan was suffering from its military defeat and economic struggles. Kurosawa was a great fan of American Westerns, and he was greatly influenced by American directors of this genre such as John Ford, Howard Hawks and Abel Gance (Cousins, 2011). The striking use of the landscape, and the framing of masculine heroes against the wide American sky are features that Kurosawa admired in American western films, and he married this with his own understanding and knowledge of Japanese martial arts. Instead of the canyons and cacti of American Westerns, Kurosawa shows his heroes against the more diminutive landscapes of Japan, in which the protagonist appears larger than life, as seen in this screenshot from Yojimbo:

Screenshot from Yojimbo (Kurosawa, 1961)

Kurosawa draws on Japanese literary themes to create films that are like heroic epics (Villarejo, 2013). The significance of the Samurai culture is shown in the detailed mise en scène, complete with traditional Japanese architecture and the elaborate costumes of the Samurai. The characterisations of honourable behaviour, is somewhat alien to a non-Japanese audience, and this is another reason why the films certainly do not look like the American western titles that so inspired Kurosawa. Nevertheless, there are some elements in common, such as the recognition of the human side of these ancient stories. Kurosawa’s characterisation sometimes inserts ironic or comic touches, showing a character who is lazy for example, and this reminds the audience that the world of the Ronin is to some extent idealised, and that the reality of human experience can never live up to the high standards that the warrior ethos demands. These deep themes, that a part of Japans military history, are given a new twist in Kurosawa’s work. For me, it is this bittersweetness that reminds me of the American western genre. Samurai and cowboys are both obsolete categories in the modern world, and yet there is something fascinating and enduring about the way these films try to capture the fading glory of the past.

An example of how Kurosawa blended this mixture traditional and modern was in how he vividly shot The Seven Samurai with the most advanced long lenses available, edited it superbly so that the viewer is drawn into its well-orchestrated and motivated action (Cousins, 2011). This director clearly had a deep appreciation of film as an entertainment form, as well as a historical or artistic production (Nowell-Smith, 1997). Kurosawa was popular in Japan because of his traditional, Japanese themes, such as the nature of the Ronin and his struggle to overcome his own weaknesses as well as the challenges he meets in the world. His inclusion of elements of the American Western appealed also to non-Japanese audiences, however, and it is this fusion of different elements that makes him stand out as an internationally famous film director.

The very long running time of Seven Samurai (1954), at 198 minutes, forces the audience to think about the action that is taking place on the screen. The director is not in a hurry to get through the plot, and this gives him time to explore a variety of deeper themes, such as for example, the futility of violence and the pointlessness of honour feuds that go on from generation to generation without any kind of resolution. Screenshots such as Figure 2 below, show the intense focus on character, inviting the audience to weigh up the decisions that are being made, and identify with the characters’ strengths and weaknesses.

Figure 2: Screenshot from Seven Samurai

Turning now to Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964), it is obvious that this director was a fan of both the classic genre of the American western and Kurosawa’s innovative treatment of this genre. These two styles influenced his work, and he added his own fascination with very large close-ups, which he used to draw attention to the characters in the film on a visual rather than verbal level. The technique is not the same as traditional Hollywood close-ups in love scenes, for example, or during key dramatic speeches, where the focus is on the dialogue, but it is reminiscent of Kurosawa’s technique. The man with no name in A Fistful of Dollars is characterised by his silence and his striking physical appearance. The director maintains a degree of mystery around the man’s thoughts and lets the viewer make up his or her mind simply by looking at his rugged face, held by the camera for a long time. This lingering camerawork then contrasts sharply with the fight scenes, which are fast and bloody.

Figure 3 below illustrates the way Leone uses a combination of costume and setting to frame his central character in a memorable way. The backdrop is classic western scenery, but Eastwood’s poncho changes the classic cowboy silhouette into something much more ambiguous. There is an exotic dimension to his appearance, as if he is a kind of international cowboy, no longer pure American hero, but now taking on Latino qualities as well.

Figure 3 Screenshot from A Fistful of Dollars (Leone, 1964)

With A Fistful of Dollars brought creative innovations in the way the film is scored, it has extended melodic lines, often with an inspiring soprano voice, to accompany scenes of very brutal violence (Nowell-Smith, 1997). This juxtaposition is shocking, and adds greatly to the impact of these scenes.

These two directors each appropriate elements of the Western genre in their own way and fuse them with Japanese and Italian dimensions respectively. Both are keen to cross the boundaries of history, geography and language, to depict some universal ideas about what it means to be a man, to fight, and to experience all the ups and downs of human life. It is their ability to innovate while preserving the essence of traditional genres and stories that gives these directors cult status and a permanent place in the history of film.

Bibliography

Cousins, M. (2015). The story of film. 2nd ed. London: Pavilion.

Doughty, R. and Etherington-Wright, C. (2011). Understanding film theory: Theoretical and critical perspectives. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hutchinson, R. (2017). A Fistful of Yojimbo: Appropriation and Dialogue in Japanese Cinema. World Cinema's 'Dialogues' with Hollywood, [online] pp.172-187. Available at: http://www.academia.edu/3126843/A_Fistful_of_Yojimbo_appropriation_and_dialogue_in_Japanese_cinema [Accessed 25 Apr. 2017].

Kurosawa, A. (1954) Seven Samurai. [Film] Japan: Toho.

Kurosawa, A. (1961) Yojimbo. [Film] Japan: Kurosawa Production/Toho.

Leone, S. (1964) A Fistful of Dollars. [Film] Italy/United States: Jolly Film/Constantin Film/Ocean Films.

Nelmes, J. and Wells, P. (2012). Introduction to film studies. 5th ed. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Nowell-Smith, G. (1997) The Oxford History of World Cinema. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thomson, D. (2014). The New Biographical Dictionary Of Film 6th Edition. 1st ed.

Villarejo, A. (2013) Film Studies: The Basics. Second edition. Abingdon: Routledge