HNC Photography, IFC - Coursework, Introduction to Film Culture Blog, Movies watched, Part four - Rites of passage, Project 4 - Twenty-first century folklore, Research & Reflection IFC

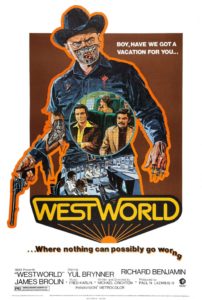

Westworld (1973)

Director: Michael Crichton

Director: Michael Crichton

Cast: Yul Brynner, Richard Benjamin, James Brolin:

Summary: A robot malfunction creates havoc and terror for unsuspecting vacationers at a futuristic, adult-themed amusement park.

Reflections and Analysis:

The portrayal of ‘masculinity’ in the film

Representations of masculinity are central to Westworld, wherein the film’s protagonist, Peter, recognises the need for masculine traits if he is to overcome his android nemesis. This emphasis on masculinity was commonplace in an era which gave us iconic masculine characters Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry. As the plot progresses, the once timid Peter becomes increasingly accustomed to the type of machismo and ruthless masculinity that inhabits the theme park in which the film is set—Westworld is all about brutality, a common trait in cinema which depicts hyper-masculinity (Etherington-Wright & Doughty, 2011, p.179). This is encapsulated by the final scene, where Peter sits triumphant on the dungeon steps, fresh from his physical conquest of the machines—where once he was stalked by the gunslinger, now he is the last man the standing, the epitome of the Western icon.

Westworld relegates women to the role of the damsel in distress, or the floozy, sexbot. However, like the emphasis on hyper masculinity this trend was common in the Sixties and Seventies Hollywood”—men were the heroes, women the dehumanised sex objects. Large portions of Westworld present the ideal setting for a portrayal of masculinity as it was seen in that era—the Seventies saw the rise of the Western as the quintessential masculine genre, both in film, and right across other forms of popular entertainment. Westworld is no different in its portrayal of masculinity—the technicians are all male, the gunslinging androids are all male, and the protagonist survives because he becomes more of an idealised male.

The significance of Peter’s rite of passage

In a key scene, it is explained to Peter and John that the park’s scientists “haven’t perfected the hand yet” (Crichton, 1973). This revelation leads leaves the “striving for a clear differentiation of men from machines, a differentiation that is pointedly not provided” (Bakke, 2007). This lack of differentiation is symbolic of Peter’s rite of passage—to overcome the machines, he needs to aspire to the violence and hardened masculinity that they represent. In many respects, this rite of passage is a cinematic cliché; the hero has to match the ruthlessness of the villains if they are to be overcome. At no point does the film try to conjure any sympathy for the androids—the entire focus is on whether or not Peter will aspire to be the man that, as the protagonist in this genre, he was clearly born to be. Again final scene shows Peter sits on the steps of the dungeon, symbolising his escape from the social restraints that had held back his masculinity—he is a real man now, surrounded by smoke and fire.

This cliché is reinforced by the role of John, who, the more seasoned of the two, would expect to outlive his ally. However, it is John who dies first, duelling with the gunslinger after he and Peter first discover that the androids have become truly aggressive. With John dead, Peter has lost his more masculine companion—he is timid and alone, and so the scene is set for the clichéd rite of passage that dominated the era’s Western genre.

Does the CGI still ‘work’ in this film or does it now feel old-fashioned?

Crichton himself believed that audiences misinterpreted the film—for him, it was about corporate greed, but as she said, in an interview, that felt most viewers treated it as a warning on the future of technology (Yakai 1985). This was possible because of the film’s special effects, which, while limited, still hold up today. Westworld was the first feature film to make use of digital image processing, one of the first technologies to be used by cinema for special effects (Nelmes, 2012,). Prior to the innovations of Westworld, most special effects had relied on photographic plays on motion (Villarejo, 2013,), and so Crichton’s work is considered by many to have “pioneered” modern special effects:

The movie’s use of a digital effect for a total of two minutes—a now-routine process called pixelization, commonly deployed on Gordon Ramsay cooking shows to obscure a contestant’s cursing mouth—was the unlikely launching point of this revolution. (Price, 2013).

Beyond these two revolutionary minutes, much of the production is filmed as live action. As noted by Price, Westworld stands up to contemporary scrutiny because, unlike “the digital effects of today’s films, which routinely use effects to try to reproduce reality, or fantasy-reality, those of the ‘Westworld’ era were much more modest in purpose” (Price 2013). In many respects, it is not quite a fair comparison to hold the film’s special effects up to contemporary standards, as it was not heavily post-processed, relying instead on live action. What it did do computationally, however, it did with considerable success, representing the perspective of the android in a pixelated fashion that would still be acceptable to contemporary audiences, as demonstrated by Price’s treatment of the film. One of the challenges of old films being watched by contemporary audiences is that they have to portray technologies and instruments that we now have, and their projections are often inaccurate—futuristic computers, for example, do not look anything like the computers of the future. However, because Crichton used his special effects to represent the android’s view of the world, contemporary audiences, still unfamiliar with androids, have a greater ease accepting the film’s representation of a phenomenon that, decades later, is still the realm of fantasy.

Bibliography

Bakke, G. (2007) Continuum of the Human. Camera Obscura. 6661–78.

Bordwell, D. & Thompson, K. (2013) Film Art: An Introduction. New York, McGraw-Hill.

Crichton, M. (1973) Westworld.

Etherington-Wright, C. & Doughty, R. (2011) Understanding Film Theory. New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

Nelmes, J. (2012) Introduction to Film Studies. New York, Routledge.

Nowell-Smith, G. (1997) The Oxford History of World Cinema. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Price, D.A. (2013) How Michael Crichton’s ‘Westworld’ Pioneered Modern Special Effects. [Online]. 2013. The New Yorker. Available from: http://www.newyorker.com/tech/elements/how-michael-crichtons-westworld-pioneered-modern-special-effects [Accessed: 11 April 2017].

Quiring, L. (2013) Dead Men Walking: Consumption and Agency in the Western. Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies. 33 (1), 41–46.

Villarejo, A. (2013) Film Studies: The Basics. New York, Routledge.

Wills, J. (2008) Pixel Cowboys and Silicon Gold Mines: Videogames of the American West. Pacific Historical Review. [Online] 77 (2), 273–303. Available from: doi:10.1525/phr.2008.77.2.273.

Yakai, K. (1985) Michael Crichton / Reflections of a New Designer. Compute!. pp.44–45.